Key insights from

In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction

By Gabor Maté

|

|

|

What you’ll learn

In the Buddhist mandala, there are six realms of life, each characterizing a different aspect of human experience. “The realm of hungry ghosts” is a state of being in which we pursue external things in hopes that they will satisfy our deep inner longings. In the artwork, these hungry ghosts are depicted as scrawny, malnourished people with thin necks, frail bodies, and hunger-bloated bellies. This is the realm of addiction, where substances, objects, and activities are compulsively pursued to hide an ache.

As Hungarian-Canadian psychiatrist and researcher Gabor Maté puts things in his award-winning book, addiction is a state in which “we haunt our lives without being fully present.” Maté’s own passion and expertise in the addiction field come from decades spent serving the forgotten down-and-outs of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside—essentially a Canadian version of Skid Row. It’s the side of town filled almost exclusively with hungry ghosts, and he advocates passionately for an intuitive, but unconventional approach to treating them. Maté stresses, however, that addictions take many forms, some that hit uncomfortably close to home.

Read on for key insights from In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts.

|

|

1. Addiction is far too complex to sum up as a “disease” or a “moral failing.”

What do we have in mind when we say the word “addiction?” In today’s usage, “addiction” most commonly refers to distinct behaviors (gambling, sex, drugs, or alcohol). But this definition of addiction has only been operational for about 100 years. The term “addiction” has been around a lot longer, and it’s been used simply to describe an activity that someone is really passionate about, a goal into which you invest significant time and energy. It’s not confined to a negative pattern of action. Writers like Shakespeare and Cervantes and politicians from several centuries ago would use “addiction” to connote a positive ambition.

The more ancient Roman usage of the word addictus referred to a person who couldn’t pay off his debts. Such a man had become “addicted” to his creditor. In that context, addiction meant enslavement, which speaks better to our current moment, in which we see addiction as a kind of enslavement to a pattern of behavior.

Clinical settings tend to stress addiction’s persistent, compulsive aspects, and actions a person repeatedly takes even in the face of harmful consequences to self and others. Definitions like these have their place, but they're narrow. People are addicted to all kinds of things and activities—even if those activities don’t land them in jail or on the streets. To more fully understand addiction and the fundamental processes involved, we need to think beyond junkies hunting for crack cocaine in back alleys or the Monday night drunk. There are plenty of behaviors that are not linked to substances that can be extremely damaging to physical health, mental health, and relationships with others.

The hallmarks of any addiction are compulsiveness, compromised self-regulation, habitually falling into it even in the face of harm, lack of satisfaction, and increased irritability when substances or activities are not available.

All addictions utilize the brain circuits and chemicals. To really understand addiction, we can’t view it as a psychological or spiritual issue divorced from the physiological. Addiction is a complex phenomenon that connects social, spiritual, political, economic, psychological, sociological, neurological, and emotional: Each of these lenses is fully necessary to account for addiction. This complexity is the reason that calling addiction a “weakness of the will” or a “disease” is inadequate. It’s not “just” a moral or medical issue. It’s not just anything. At bottom, it’s an attempt to avoid an inner void, but the reasons that void is there and the ways one tries to avoid it are as varied as people themselves.

|

|

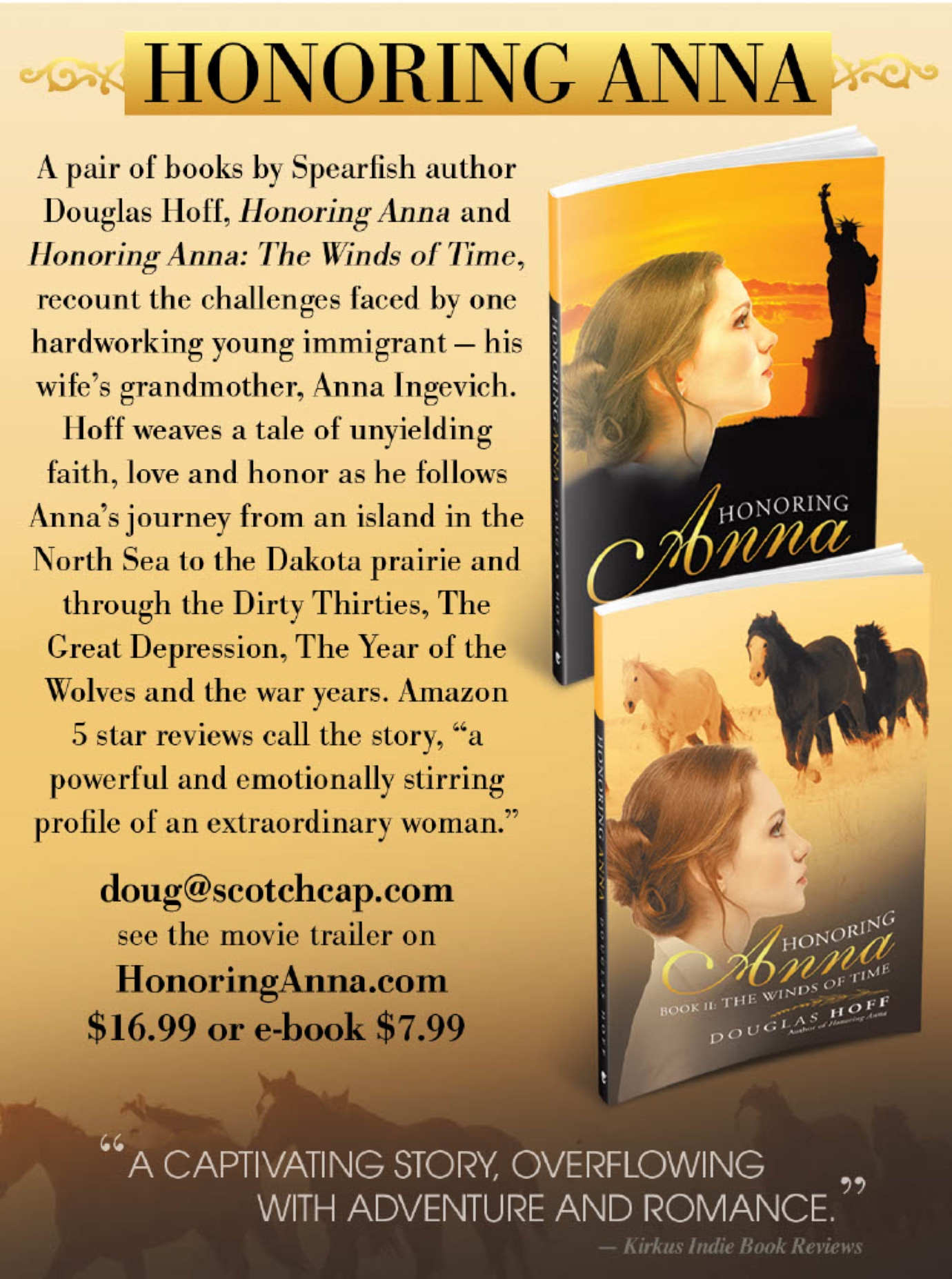

Sponsored by Honoring Anna

Amazon 5 star reviews.

Spearfish author, Douglas Hoff, weaves a tale of unyielding faith, love and honor as he follows Anna's - a young, hardworking immigrant - journey from an island in the North Sea to the Dakota prairie and through the Dirty Thirties.

|

|

2. Some addictions are shunned while others are celebrated.

Maté often reflects on the uncomfortable similarities between his patients and himself. Most of Maté’s patients are addicted to some combination of drugs and alcohol, but he has his own addictions. Even if it’s not crack cocaine or meth, he still experiences those same patterns of craving and compulsion and relapse that his friends on Vancouver’s equivalent of Skid Row know all too well. When he describes what is happening for him internally in those moments of neediness to his patients, he is met with knowing head nods. Maté has his moments of compulsively annihilating himself by burying himself in his work or hoping for a hit of affirmation at the next conference. The content is different than that of his patients, but the process is exactly the same: Those feelings of compulsion, craving, and relapse, and trying to get rid of the self-loathing that festers in the heart of an addict—they’re familiar to the doctor as well as the patient.

Maté muses that he has emotionally abandoned his family in seasons of workaholism, but his abandonment was the kind that made him lots of money, gained him recognition, and had people cheering for the pioneering work he was doing. Whatever prestige certain addictions carry, and whichever ones we overlook, they are still addictions.

No matter how broken or down and out someone is, there is not a single person on earth who is empty and lacking to the core of their being. But this sense of intrinsic inadequacy is how addicts experience themselves. In an exercise of heartbreaking futility, they cover up that experience of perceived emptiness with addictive patterns. The problem is much less what they pursue than the way they pursue it.

The massive amounts of energy devoted to covering up this deep sense of inadequacy exhaust precious psychological and spiritual resources, and stunt genuine growth. As one long-time addict and inmate-turned-writer put it, “It has seemed to me at times that you can be present in your life only as a kid or when you’re on heroin.” This puts words to an unspoken script that many discouraged individuals act out, whether they’re in prison for their runaway compulsions or whether their compulsions have earned them a nice house and admiration.

|

|

3. Addiction-prone personalities lack clear boundaries, struggle to self-regulate and control impulses, and believe they are inherently unlovable.

The notion of pursuing external things and not internal things is central to what is often called the addictive personality. We’d be more precise to call it the “addiction-prone personality.” Obviously, there’s no assortment of personality traits that’s going to inevitably lead someone to addiction in and of itself, but there are some clusters of traits that make it much, much more likely that someone will relate to an activity or a substance in a way that becomes compulsive and out of control. If your personality is such that you compulsively look for emotional or physical comfort in external sources, you could be someone who is more susceptible to the addiction process.

The addiction-prone personality reflects a struggle to self-regulate. By self-regulation, we mean the ability to distinguish between the self and one’s own feelings in a given moment. Children do not have this ability. They are their emotions, which is why they’re entirely in need of parents to give them a sense of self, and assure them that they are okay. They need that external parental source to soothe them and calm them down because kids at a young age can’t control their emotions.

For many adults, the struggle to self-regulate remains, and the tendency to look for other sources of support outside themselves never really leaves them. Reliance on external things is the only way that they know how to make themselves feel okay, whether that’s with food, alcohol, pornography, video games, extreme sports, or finding a steady stream of love and attention from other people—the list goes on.

A key part of self-regulation is impulse control. This is another area of struggle for the addiction-prone personality. When strong feelings suddenly rise up—whether they’re excitement, fear, or anger—the addiction-prone personality doesn't know what to do with them.

A lack of differentiation is another aspect of the addiction-prone personality. In other words, the boundaries between self and others and self and one’s own inner experience are fuzzy and indistinct. So if you have differentiation issues, whatever you feel, you are, or whatever someone else is feeling, you take on as your own emotions. If someone near you is experiencing heavy anxiety, that person’s anxiety becomes yours. When there’s an inability to know what belongs to whom, excess emotional energy builds up. Without the ability to regulate that, you’ll likely look for an outside source to provide some comfort and stability. This is what we do when we’re unable to hang onto our sense of self while interacting with other people.

The hallmarks of the addiction-prone personality are the struggle to self-regulate and to control impulses, a lack of basic differentiation, an unhealthy sense of self, and the deep belief in one’s intrinsic emptiness. Ultimately, it’s a lack of emotional maturity. This maturation process is developmental, but many kids never hit these milestones of emotional maturity. Many adults don’t either. Thankfully, adults can continue to grow and develop emotional maturity even if it was not instilled in them as children.

|

|

|

|

4. Early childhood environment impacts brain development far more than genetics.

It’s hard to talk about addiction without talking about brain development. And it’s hard to talk about brain development without also talking about the early childhood environment. A common theme among the addiction-prone is a traumatic upbringing and incomplete brain development.

In the early 1990s, President George H.W. Bush called the coming decade “the decade of the brain.” He was right. In the United States and elsewhere, there was an enormous surge of research on the brain that shifted key paradigms. Scientists were forced to discard some old understandings of how the brain worked. Yet there remains a great deal to be discovered about the inner workings of the brain. Some experts opine that we need centuries’ worth of research.

Whatever else remains to be discovered, the general outlines of the existing research are becoming crisper, and the findings have blown open the nature-nurture debate—in favor of nurture: Early childhood environment is a stronger predictor of brain development, emotional stability, and life satisfaction than genes.

Even the best genes in the world won’t make a difference without an environment where the right neurological circuits, networks, chemicals, and systems can be established. Think of the world of agriculture: Say you have a seed that you’re about to plant, a seed containing the most ideal genetic material available to produce that delicious fruit or vegetable. Without the proper conditions, like nutrient-rich soil, adequate water, plentiful sunlight, and a moderate temperature, the plant can’t grow and reach its full potential. Say you have two of those seeds, and you plant one in an ideal environment with everything it needs to thrive and you plant the other in a spot that gets little water or sunlight. Even if the genetic material is exactly the same in both seeds, you will still end up with two very different plants. The same holds true when we talk about children and their developing brains.

The main systems in the brain that drive addiction processes are the attachment reward system, the incentive-motivation system, stress systems, and the prefrontal cortex regions that relate to self-regulation. These are all heavily shaped by environmental factors. To give just one small example, studies have found that, from rats to humans, the mammalian brain reaches optimal potential when the young are stroked and cuddled and held—or, licked, in the case of rats. The more cuddling, the stronger the circuitry that reduces anxiety. Babies that were cuddled more also tend to have more receptors for benzodiazepine, a chemical that naturally calms the stressed brain.

So for anyone who wasn’t held and cuddled at all by mom as an infant and young child, anxiety is likely going to be much higher. The brain doesn’t have nearly as many receptors that transmit the calming chemicals. Studies like these can help us understand the addict’s world better and extend more compassion. People who take to the streets searching for dollar-per-pill benzos to calm their rattled nerves are looking for a little bit of relief because their bodies don’t produce those chemicals on their own. This hunt for artificial tranquilizers tells us less about “weak wills” and more about childhood deprivations and trauma. Their brains never really stood a chance.

Thankfully, early childhood environmental experiences, while formative, are not destiny. Neither is genetics. The brain is a robust organ that will heal if given the opportunity, and it’s never too late for new circuits to be developed. Moreover there’s something about us beyond the wirings and the firings and the flow of chemicals, something almost spiritual that never dies even in deep addiction.

|

|

5. Maté’s experiences in Vancouver’s Skid Row made him a believer in harm reduction policies.

What is harm reduction? It’s a holistic approach to the drug problem that goes beyond simply advocating cold-turkey abstinence from drugs and punishing those who fail to abstain. It’s a more relational tack that offers some combination of housing, safe injection sites, legal prescription alternatives like methadone to replace their dependencies on contrabands, as well as sites to swap out used needles for new clean needles—reducing complicating factors like HIV and Hepatitis C.

Ultimately, harm reduction is about providing an environment that is accepting and hospitable enough to reduce their suffering, where addicts form relationships with caretakers, and that provides them with the external and internal resources needed for someone to truly stop using.

Maté’s introduction to harm reduction came while he served as a psychiatrist with a Vancouver non-profit called the Portland Hotel Society. This organization serves the addiction community in Eastside by converting former luxury hotels into functional domiciles where the “nonhousable” can stay for free. The nurses took Maté to one such hotel to see a 30-something year-old man from Quebec who was, by all accounts, “a difficult patient.” When Maté entered the hotel room, the patient was swearing as he attempted to inject his neck with some unknown cocktail. He was on the verge of seriously injuring himself, so Maté offered to help him inject more safely. He asked the nurses to prepare a tourniquet for the man’s arm, and coached him on how to make the vein more prominent in his arm, so the man could inject the mystery liquid—whatever it was—more safely.

Maté could hardly believe himself in that moment. Was he really helping a patient self-inject an illegal, mind-altering substance in a roach hotel? But then he wondered what the alternative would have been. The medical team could have tried to persuade the patient not to use this time. But that would have been far from the cure that was needed. It was more strategic at that moment to communicate to the patient, “We care about you.” He was going to use, no matter how eloquent their dissuasion, so why not equip him to do it in a way that wouldn’t bring him more harm than he was already in? Building this bridge of trust opened that patient up to greater trust and openness to medical advice in the future, which led to further conversations about his past wounds—the real source of the addictive behavior.

Sadly, this particular patient died years later of conditions linked to HIV, but the harm reduction approach prolonged his life far beyond what it might have been without the medical staff’s support and relationships. It also improved his quality of life, and alleviated some of his suffering along the way. In a place like Downtown Eastside, not every story is going to end happily. Life is messy, and it would be naïve to expect a cure-all. Still, harm reduction is the best chance for stories of triumph and not just stories of tragedy.

|

|

6. Harm reduction gives addicts a better shot at long lasting recovery than the threat of harsh punishment.

When some people hear “harm reduction,” they think of a coddling, enabling program that perpetuates addicts’ habits rather than curing them. But those who think being cured from an addiction is simply no longer using drugs and staying away from alcohol haven’t understood the nature of addiction.

For the people in downtown Eastside, full-fledged addiction is (among many other things) a medical condition they have had for years. But the hungry ghost condition is also made possible (and made worse) by a lack of meaningful relationships and support, deep self-hatred, and consistent rejection from more “acceptable” members of society. And punishing the addicted or letting a friend overdose “to teach them a thing or two” actually teaches them nothing. The parts of their brains that process information and plan effectively are offline, and most are unable to think beyond the next hit and basic survival needs. Punishment isn’t nearly as instructive as people suppose.

To be clear, there is no magic bullet for getting rid of an addiction. Health care services can’t do much to resolve these deeper issues, but they can help with some of the symptoms and suffering that the addicted suffer—not to mention the pain of marginalization that drug addicts commonly experience.

One of the common objections to reducing the harm and suffering that addicts experience is that they are undeserving of such treatment. “They’ve made their bed, so let them sleep in it” is the guiding logic. But how different is that from saying, “Doctors shouldn’t treat chronic smokers for their bronchitis and emphysema, nor adrenaline junkies who break their limbs on ski slopes or cliffs, nor morbidly obese individuals for their cholesterol and heart issues.” No doctor and few people would expect the medical system to withhold care because these issues were self-inflicted, but many people have serious misgivings about treating addicts in suffering.

Harm reduction is not choosing coddling over tough, punitive love. It’s the decision to play the long game instead of the short game. People mistakenly assume that harm reduction measures have given up on abstinence, but nothing could be further from the truth. Harm reduction holds out hope for a true abstinence, one that comes because drug addicts have found something better, like meaningful connection, trusted community, and alternatives to compulsive behavior. But people employing harm reduction measures also recognize that someone neck deep in a habit on Skid Row is in a lot of pain—and at this moment they probably lack the support and emotional and spiritual resources to cold-turkey abstain without falling right back into this or another harmful habit.

In a word, harm reduction tries to create an ecology of healing. It’s more holistic. It attempts to create an environment of acceptance, a place of trust, where the patient can begin to believe that, “Even if I inject in this safe site that’s been set up for me, these people don’t look at me differently.”

Harm reduction is not just policy. It’s also an attitude of hospitality toward those whom society tries to forget. By cultivating an atmosphere of hospitality and acceptance, there is opportunity to repair some of the deepest wounds in addicts, the very wounds that are the biggest blocks to true abstinence in the first place.

At the core of every addiction is the compulsion to avoid an inner void. Everyone has those—not just the street-involved of Eastside stealing and prostituting their way into their next hit, but a political power-craver looking to win an election, a workaholic burying himself in his job, or a shopaholic who can’t stop buying more clothes. Part of improving the situation for drug addicts is to recognize that, at our roots, we are not all that different, that their struggle is our own.

|

|

Endnotes

These insights are just an introduction. If you're ready to dive deeper, pick up a copy of In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts here. And since we get a commission on every sale, your purchase will help keep this newsletter free.

* This is sponsored content

|

|

This newsletter is powered by Thinkr, a smart reading app for the busy-but-curious. For full access to hundreds of titles — including audio — go premium and download the app today.

|

|

Was this email forwarded to you? Sign up here.

Want to advertise with us? Click

here.

|

Copyright © 2026 Veritas Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved.

311 W Indiantown Rd, Suite 200, Jupiter, FL 33458

|

|

|