Key insights from

Letter From Birmingham Jail

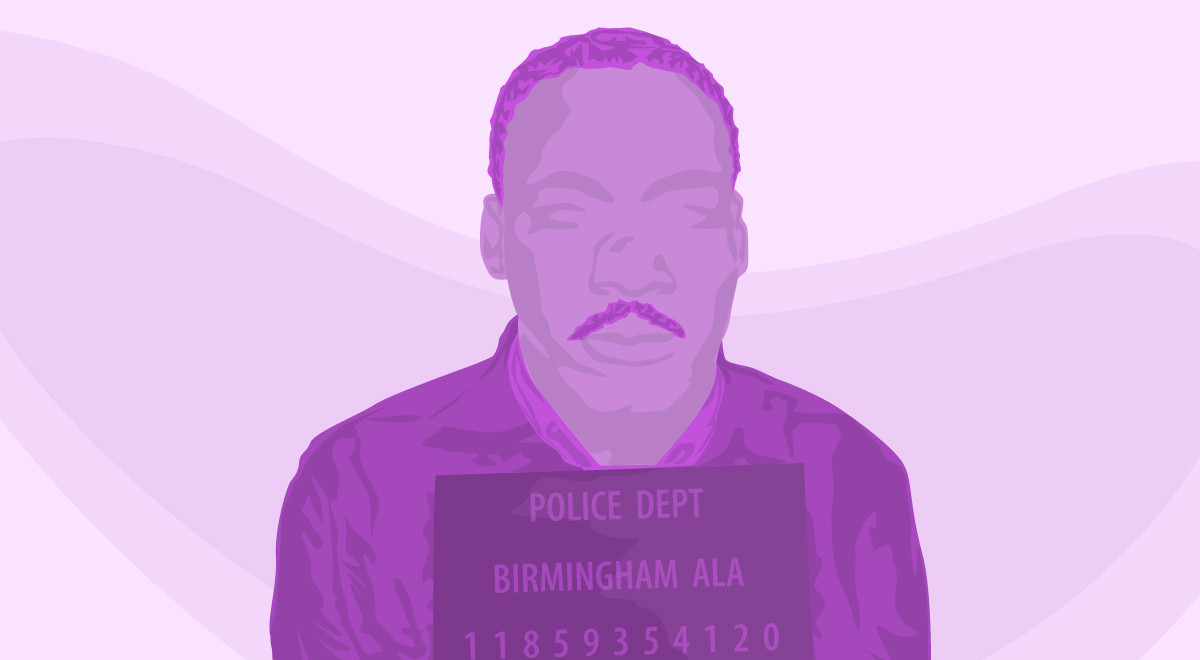

By Martin Luther King, Jr.

|

|

|

What you’ll learn

A group of clerics from Alabama wrote a piece criticizing the civil disobedience of King and others. This essay-letter was King’s response, written in the margins of newspapers as he sat in his jail cell.

Read on for key insights from Letter From Birmingham Jail.

|

|

1. A successful nonviolent movement will contain four steps.

A nonviolent campaign begins with the collection of relevant facts. The evidence is clear that Birmingham, Alabama, is drowning in segregation and injustice. It’s arguably the most segregated city in the nation. In Birmingham there are more unsolved cases of black homes getting bombed than anywhere else, and the courts routinely withhold justice from blacks.

The second step in a nonviolent campaign is negotiation. With the facts gathered, the Negro community has sought to bring its grievances to city leaders. But leaders have consistently rebuffed attempts to negotiate.

The unwillingness to negotiate necessitates nonviolent, direct action, but before undertaking such action, those who will be involved undergo self-purification, a process of mental and spiritual preparation for the action ahead. In trainings, people ask each other over and over if he or she is prepared to receive blows without responding in kind, or to do time in jail.

The fourth step is nonviolent direct action, which involves peaceful protests, sit-ins, and so on. These are acts of presenting bodies as sacrifices, in the hopes of awakening regional and national consciences.

Some have criticized this approach, asking if there is a better way. There’s no question that negotiation is preferable to direct action, but direct action is undertaken with the aim of opening up a space for negotiation. Negotiations haven’t worked, however, which is why nonviolent direct action is necessary and warranted. It gets the attention of communities that have refused to negotiate, with the goal of getting them to come to the table and take an honest look at the problem.

|

|

2. Tension is not categorically evil.

“Tension” is a provocative, jarring word for many. Good! It’s also a fitting word. While tension that comes from violence is to be avoided, tension arising from nonviolent action is appropriate. Growth does not come without tension, and tension can be constructive and beneficial.

Socrates was called the gadfly of Athens because he didn’t shy away from thought-provoking discussions. His questions stirred up internal tensions in others, but this was in the hope of freeing them from falsehoods and empty platitudes.

In our own time we need some creative gadflies who look at societal problems in a measured way and create tensions in the hopes of illuminating the dark ignorance of prejudice. When we create crises through tension, negotiation is much more likely.

For too long, the South has tried to conduct its affairs through monologue, but it’s time that changed from monologue to dialogue.

|

|

3. The word “wait” comes easily to those who have never felt the pain of segregation.

Many have criticized the nonviolent protests in Birmingham as coming at the wrong time, but the truth is that, compared to many other countries around the world, the United States is moving toward democracy very slowly. When you’ve never known the sting of segregation, advising the Negro to wait is very easy.

But when your mothers and fathers are getting lynched; when your brothers and sisters are capriciously drowned by mobs; when policemen curse, kick, or even kill your family members; when you are at a loss for words explaining to your daughter why she won’t be able to go to the new fair advertised on TV or when your son asks why white people are so mean to colored people; when you see even young children developing a sense of inferiority and unconscious resentment toward whites; when you sleep in your car because motels turn you away; when you live your life constantly walking on egg shells, apprehensive and unsure of what to expect next; when you have to fight the belief that you are less than someone with lighter skin; when you are called “boy” whatever your age; then you will understand why the Negro community refuses to wait, and why these nonviolent actions are just.

Words like “wait” and “eventually” have come to mean “never.”

|

|

|

|

4. It is just to obey just laws, and it is just to disobey unjust laws.

Many whites, even many clergymen, have expressed a kind of trepidation over the laws that are being broken through civil disobedience. They are right to point out the importance of following laws, but we must distinguish between two kinds of laws: just laws and unjust laws.

We are legally and morally obligated to obey just laws. Just laws are those man-made laws that coincide with the eternal, divine law. Unjust laws are man-made laws that are at odds with those moral standards. As Saint Augustine put it, “An unjust law is no law at all.”

Saint Thomas Aquinas talked about just laws as those which enhance the human personality, and unjust laws being those which do just the opposite. The laws that uphold segregation are unjust in the sense that they diminish the personality of both segregation’s beneficiaries and victims: by inculcating a false sense of superiority in the former and inferiority in the latter.

The injustice of segregation becomes more pointed when we consider that some theologians view sin primarily in terms of separation. From this view, segregation becomes an appalling expression of human sinfulness, as it separates and isolates.

Thus, whether a law should be obeyed or not depends on whether it is a just law or not, aligned with transcendent moral standards or separated from those standards. The Supreme Court’s 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, for example, which declared segregation in schools unconstitutional, was a just decision. It is a just ruling that we should follow and would be wrong to disobey because the law strikes at the heart of a poisonous segregation. On this point, it is the segregationists who are advocating a usurpation of laws—not the Negro.

Just as important as the obedience of just laws is the disobedience of unjust laws in the hopes that new man-made laws will better align with the higher law. It is fine for a city to issue a permit for a parade, but when that law is used as pretext for barring people from the free exercise of their rights to free speech and peaceful assembly, the law becomes unjust. The most righteous action is to disobey, to break the unjust law peacefully, lovingly, openly, and with an acceptance of the consequences.

This tradition of civil disobedience extends far back into the annals of history. In Ancient Babylon, Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego exercised sober-minded civil disobedience to an unjust law in the interest of obeying a higher law than the king’s. At the risk of execution or being torn apart by lions in gladiatorial arenas, early Christians disobeyed Rome’s prohibitions that prevented their worship of Jesus. The Boston Tea Party was a pivotal act of civil disobedience against the British. And, of course, who would fault those who defied Nazi laws by hiding Jews, or the Hungarian resistance for fighting against Nazi occupation? These were deeply righteous acts.

A society is just when the law applies equally to majority and minority, when the majority not only expects the minority to follow the law, but submits to the same law as well. How can the United States consider itself a democracy when blacks are systematically barred from voter registration? There are counties in the South where not a single Negro is registered to vote—even when blacks are the majority. These elections are not democratic, and so we must continue to remind the white majority of the freedoms that living in America promises.

|

|

5. White moderates harm the cause of black freedom more than the KKK.

Half-hearted affirmation is more disorienting than blunt rejection. The Klan members are a much less formidable obstacle to the Negro cause than whites who limply support the cause in words but reject the methods. They advise to hold off with protests and other forms of direct action until a more “convenient” time. It comes across as condescending and prideful to determine the timeline for someone else’s liberation. Time is a neutral medium. Its mere passage doesn’t guarantee the change we wish to see. Progress doesn’t come through passivity, but through consistent effort and endurance, partnering with God in the work he is doing. It is never the wrong time to do the right thing.

The white moderate has shown a deep discomfort for the tension that the direct action has created. Law and order are supposed to establish justice, not stand in the way of it. Laws that thwart justice are like dams that stop up the river of progress. The tension that is unsettling the South is not the problem. The direct action that creates tension is merely pulling to the surface what has always been there. The tension has always been there—even if subterranean. Just as a cyst can’t heal until brought to the body’s surface where light and air can heal it, the cyst of racism needs to be shown for what it is. When moderates support things staying as they are, they are not promoting peace, but hoping the tension will melt away if ignored.

Criticizing the nonviolent protests for inciting violence relies on a questionable logic. Blaming resultant violence on nonviolent protesters isn’t that different than blaming a wealthy man for being robbed because he had too much money or rejecting Jesus’ profound connection to God and righteous life because they led to his crucifixion. In the same way, it would be wrong to criticize people pressing for their constitutionally–guaranteed rights because their assertions are violently rejected.

|

|

6. “Extremism” both is and isn’t a fair characterization of nonviolent protest.

It’s discouraging that clergymen would describe our nonviolent efforts as extremist. It would be more accurate to see the nonviolent direct action as situated between two groups of blacks: the contented and the militant.

The contented blacks come in two forms: those who either have resigned themselves to the status quo of “nobodiness” after a long history of oppression and denigration that has drained them of any self-respect, or those middle-class blacks who have managed to procure enough financial stability that they stop caring about the majority of their siblings and prefer that the power structures remain undisturbed. In both cases, they have come to accept segregation and have stopped fighting for the cause of black freedom. The contented blacks are not manifesting a righteous contentedness, but a perverted acceptance of injustice.

At the other extreme are the black nationalists who, far from resigning to segregation, are militantly seeking to eradicate it through violence—and to eradicate those who uphold it. They are anti-white, anti-Christian, and anti-American. Elijah Muhammad’s Muslim movement typifies this extreme. Nonviolent direct action stands between these extremes. Were it not for the way of love that the Negro hears about in the churches, Southern streets would be filled with blood. It’s worth mentioning, however, that, if white brothers and sisters continue to reject these nonviolent efforts as “extremist” and fail to support the cause of black freedom and the end of segregation, then despondency and anger will turn many Negros toward violent black nationalist expressions.

For a while the label “extremist” seemed a misunderstanding that stung. But in his own way, Jesus was also an extremist—an extremist in his love for others. In this sense, the term “extremist” becomes more palatable, because the desire to love enemies and pray for those who persecute you is nothing short of radical. We hope that through nonviolent protests, we act in love and righteousness, just as many have before us: Jesus, the prophet Amos, Martin Luther, John Bunyan, Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Jefferson. In their own ways, they were radicals, demanding a more righteous way of ordering society. What the South, the country, and the world need more than anything are creative extremists.

|

|

This newsletter is powered by Thinkr, a smart reading app for the busy-but-curious. For full access to hundreds of titles — including audio — go premium and download the app today.

|

|

Was this email forwarded to you? Sign up here.

Want to advertise with us? Click

here.

|

Copyright © 2026 Veritas Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved.

311 W Indiantown Rd, Suite 200, Jupiter, FL 33458

|

|

|