Key insights from

Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don't Know

By Adam Grant

|

|

|

What you’ll learn

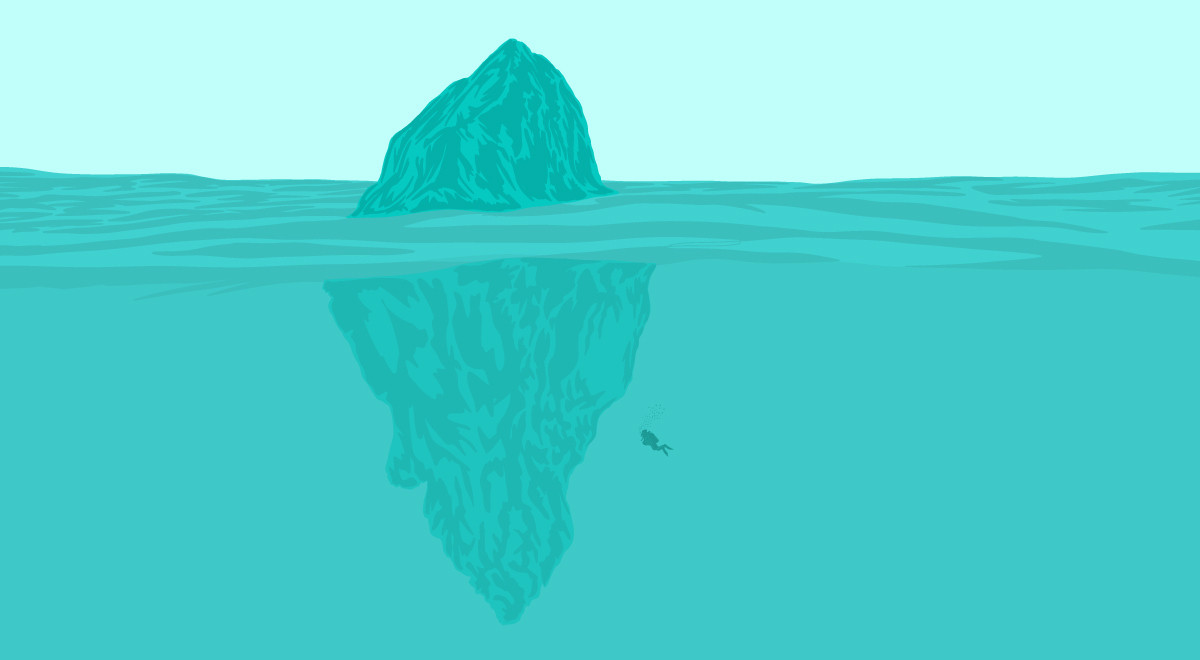

We live in a culture that shudders at the thought of being wrong—whether in the spheres of politics, sports, or daily life, most of us fail to see the areas in which we miss pertinent knowledge. Despite our tendency to idolize correctness, if we want to know anything at all, we must recognize that we are often (if not always) incorrect. Professor of organizational psychology Adam Grant helps us along, exposing the pitfalls in our culture’s desire to “know it all.” Using wisdom from psychological studies and real-world examples, Grant implores us to shed our addiction to exactitude and revel in the knowledge that what we hold in our heads will never come close to completion.

Read on for key insights from Think Again.

|

|

1. Don’t fall for the “first-instinct fallacy.” Before accepting what’s in your head, take another look.

Chances are, you’re familiar with the battle of the multiple-choice exam and the intimidating task of shading in all those tiny spherical bubbles. Research and popular opinion show that most people simply assume the first answer they pick is the correct one, preventing them from taking another look at their tests. But evidence gathered by many psychologists proves the opposite. Despite what experts identified as the “first-instinct fallacy,” or the false belief that one’s initial thoughts are right, when students took time to review their initial answers, erasing and altering them accordingly, their second choices were typically correct. The same principle holds true for every aspect of life—peering more closely at what you think you know often reveals things you would never have noticed otherwise, not to mention all those intellectual pitfalls that fly below your conscious radar.

In an era swamped with information, misinformation, and everything in between, this practice of reassessing one’s thoughts is especially crucial. One study from 2011 revealed that the amount of data filtering through the typical person on any given day is five times more than what the average person received only 25 years ago. Not only is there plenty more to learn, but there are plenty more opportunities to get things wrong, too—opening the door of one’s knowledge bank may not reveal intellectual riches but an empty vault, an unnerving revelation for anyone who thinks her mind is airtight.

To avoid this cognitive trap, people should take another look inside their minds and begin the process of “rethinking.” As one ponders the things she thinks she knows, she approaches her thoughts as a seasoned scientist would, snooping for evidence and considering her knowledge with an air of thoughtful suspicion. The scientist isn’t tied to a particular assumption without proper evidence, making her more likely to look out for instances where her thinking falls short. Moreover, this receptivity to evidence clears out preconceived notions to make room for better understanding. In a study of renowned scientists, the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi found that these intellectuals exhibited the unique trait of “cognitive flexibility.” The scientists weren’t beholden to a specific idea or thought, but moved easily between many—their knowledge didn’t get stuck in cognitive mud, but slipped fluidly from discovery to discovery.

Whether you’re taking a math exam, practicing a profession as a scientist, or simply rewriting how you perceive reality, it’s essential that you hold your mind up to the light. Examining your thoughts uproots false assumptions and yields deeper insights into the realities both within you and beyond you.

|

|

2. Humility is revelatory—without it, reality is invisible.

Whether you’re learning to paint for the first time or thinking over new ways to structure your business, the activity of uncovering something new requires humility. The author calls this process of learning the “rethinking cycle,” and it consists of four stages: At the beginning, learners must foster a degree of fault-finding “humility,” which then progresses into a state of “doubt” in which learners become dissatisfied with the extent of their knowledge. Eventually, doubt leads thinkers to a stage of greater “curiosity,” which finally drops them at the foot of pure and true “discovery.” Once complete, the process winds back toward the beginning to fuel yet another light-bulb-flashing moment of revelation.

Unfortunately, the circle sometimes has chinks. In a fascinating study by the psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, research showed that despite beginners’ lack of experience, they assessed their abilities far beyond what reality revealed. For instance, a budding guitar player fresh from only three weeks of practice might think she’s a regular Jimi Hendrix despite the fact that she only knows two chords. This oftentimes comical “Dunning-Kruger effect” is an apt warning for everyone, beginners and experts alike—it’s the subjects that people don’t know very well in which they feel a false sense of intellectual security.

To counter this kind of self-delusion, humility is essential. Though popular culture typically views the “imposter syndrome” as a mental blight, recent studies show that it may actually contribute to performance. People plagued by anxieties over their clearly excellent abilities might be able to employ those thoughts to their benefit. When learners return to a place of humility, free from thinking they’ve got everything figured out already, they grow receptive to unearthing insights and untethering themselves from where they got things wrong.

Drawn partly from the Latin word for “from the earth,” humility tills the soil of the mind and prepares every learner for fresh growth. Humility isn’t a fruitless or simply self-serving mentality. Rather, humility allows people to detect where they’ve been wrong for far too long, helping them to appreciate the knowledge and experiences of others as potent spaces for gathering new perceptions.

|

|

3. Before you disagree, find a center of consensus; conversations will be a lot more reasonable and much less awkward.

A valuable conversation about a challenging topic is an endangered breed of speech these days. In a culture tense with dissent, people could use a little help reassessing the way they speak to each other, especially when talking with those who hold differing opinions. World-renowned debate champs definitely know how to have a conversation—albeit an intensely speedy one, and they have some (rapid fire) words of wisdom for a culture that’s grown loud in contempt and mute in compassion.

In an examination of professional negotiators, consultant Neil Rackham found various practices that proficient speakers employ, which are seen in the arguments of world class debaters as well. Before delving into their points, productive speakers first find particular areas of consensus where their beliefs and those of their rivals intersect. Moreover, these arguers don’t drown the opposing side in a stream of some brilliant and other not-so-brilliant points as to why they’re right; rather, they choose fewer, stronger explanations to pitch their ideas. Often, when listeners hear a deluge of arguments, they latch onto the flimsiest one, framing the entirety of the opponent’s claim in the light of one poor bit of reasoning. The successful arguers also exhibit a greater awareness of the other side’s position, making adequate space for honest questioning. The author poses one of these questions frequently, and it may be helpful in your next dinner table rumble. When you arrive at an impasse in a disagreement, instead of simply changing the topic, acknowledge the area of disparity and ask: “What evidence would change your mind?”

A disagreement doesn’t have to result in an argument; having a mutually beneficial interaction should look a lot calmer than it often does today. Moreover, good conversations should begin with a joint effort to talk toward what’s real rather than a divisive desire to demolish another person’s argument. When interactions are approached with the same kind of humility that begins the author’s “rethinking cycle,” they take on a new shape and tone.

The typical belief that people must appear steadfast in their arguments just doesn’t cut it—rather, when an arguer is more inclined to agree, withhold, and hear others, her message manages to squeeze through the otherwise self-serving air of dissension toward a conclusion that might actually resemble peace.

|

|

|

|

4. Dichotomous thinking damages our perception of reality—answers are rarely one-sided.

Many people avoid verbal conflicts or intense controversies, but others seem to swarm straight into the mayhem like moths to light. The psychologist Peter T. Coleman facilitates a place for these kinds of people at the Difficult Conversations Lab at Columbia University. Compiling pairs of volunteer arguers, Coleman endeavors to identify what makes a typically heated conversation cool with mutual comprehension. Through this research, Coleman found that when people read an article on a particular issue that revealed the various interrelated details of a problem, they were more likely to come to an understanding. Meanwhile, when the volunteers read an article that placed the issue into two simple, competing streams of thought, they fell prey to what psychologists call the “binary bias.” Even when participants glimpsed both sides of an issue, they still siphoned a plethora of concerns into a false dichotomy.

For instance, climate change is an issue of (often uncomfortable) political debate. Why should a topic that concerns the wellbeing of the planet spawn such intense bipartisan controversy? Well, the truth is, it doesn’t—not really, at least. A 2019 poll revealed that climate change is a much less cut-and-dry political divide than the media makes it out to be. Instead of a duel between two opposing forces, the constituents of climate change fall into one of at least six categories: those who identify as “alarmed” at the situation comprise 31% of Americans, whereas those who are “concerned” occupy 26%, and the rest of the percentages taper off. Everyone else fills the labels of “cautious,” “disengaged,” “doubtful,” and “dismissive.” This last group is composed of a mere 10% of the population. And yet, this small, defecting percentage receives a vast majority of the attention, 49% more than experienced scientists did in one study, keeping many people from moving toward a solution and diluting the issue to a mere piece of political propaganda.

Contrary to culture’s tendency to split otherwise complicated issues into two simple, politicized solutions, a dose of uncertainty is necessary to perceive these situations clearly. When concerns are expressed as the complicated tangles of evidence they are, people grow more apt to listen and seek more information and understanding. When the media, politicians, scientists, and culture at large admit that their conclusions aren’t nearly as soundproof as they craft them to appear, people become more amenable to hearing the actual issue at hand.

Another feature Coleman uncovered when he assessed the best conversations at his lab was the presence of diverse emotion. The arguers who reached more peaceful conclusions demonstrated a deeper and wider emotional response than the more combative volunteers. Recognizing and harnessing seemingly contradictory feelings enables conversations to break into a new, oftentimes foreign territory—one in which deep issues don’t crumble into superficial and isolating answers and agreement becomes more than just some absurd, one-sided dream.

|

|

5. You are not your favorite sports team.

Sports rivalries are a mystery to some and a way of life to others. Most Yankees and Red Sox fans fall into the latter category, stirring up mayhem for preferences that are taken just a smidge too seriously. Brain studies show that when one’s deeply held ways of perceiving the world are under fire, like one’s sports-fueled superiority, the amygdala flames up into “fight-or-flight” mode. The mental machinery that results from this and stands against ideological invaders is aptly called the “totalitarian ego,” and it makes people less likely to question their opinions and more apt to tie who they are as people to oftentimes irrational assumptions.

What Red Sox fans, Yankee patriots, and basically everyone with an opinion must realize is that a singular preference, idea, or way of seeing reality doesn’t exhaust who they are as human beings—people are much more than that. Whether you’re engaged in a bitter baseball rivalry or a contentious political dispute, it’s essential that you refrain from associating who you are as an individual with your thoughts—taking another look at your beliefs from a distanced perspective is crucial to arriving at a truce. Failing to rethink and distinguish these untried beliefs often results in outcomes that are much more pernicious than typically harmless sports relationships. Squelching damaging stereotypes begins with identifying the intersection between belief and person to recognize the difference between the two and see where steadfast opinions are simply thoughtless assumptions.

To unbraid the bond between what you believe and who you are, it’s helpful to think of yourself in association with your important values. Rather than view yourself simply as a fiery Red Sox fan, focus on the values you hold instead, like that of sportsmanship or athletic excellence. Then it becomes much easier to see the Yankees as yet another group of humans with similar values. Moreover, the author conducted a study of these Red Sox and Yankees fans to assess what mental practices might allow their seemingly untamable rivalry to become a source of better understanding. Of all the methods he and his team tested, the one that was most successful was simple—when the baseball fanatics pondered what the author termed the “arbitrariness of their animosity,” they were more inclined to act peacefully toward their opponents.

When people recognize that many of their beliefs, preferences, and perspectives are results of happenstance, they’re better equipped to see through those passing, divisive illusions to the truth. Another psychological practice that might do the trick of disentangling truth from misperception is called “counterfactual thinking.” When a person employs “counterfactual thinking,” she envisions herself as a different person from a different background, getting a glimpse of her own opinions for what they really are. Engaging in this kind of “rethinking” is doubly impactful as it both deepens one’s perception of reality and matures one’s relationships with other people as well—even if they are those annoying fans on the other side of the aisle.

|

|

6. “Rethink” your meaning—your life is multifaceted.

Happiness isn’t stored away in a particular job title or an idealized lifestyle. Individual wellbeing is far too unpredictable to be confined to a particular life situation. Despite many people’s cravings for transcendent satisfaction, studies show that an overemphasis on the necessity of happiness causes it to dissipate. Happiness isn’t found in the widely varying locations or circumstances of life, either. Rather, research shows that striving after meaning through one’s daily habits and lifestyle is a much more sustainable way to enjoy everyday life. Though it’s definitely helpful to reassess your life decisions and available options if you’re not satisfied in a particular career path, it may be even more essential simply to take a step back and reframe your definition of that elusive thing called happiness.

The psychologists Amy Wrzesniewski and Jane Dutton studied the hugely helpful practice of “job crafting” in the hospital of the University of Michigan, where the inspiring Candice Walker worked. Candice showed remarkable kindness to cancer patients, bringing treats, sharing stories, fixing rooms, and doing other selfless, compassionate acts for people she didn’t even know. The most notable feature about Candice is that she did all of this on her own initiative. Her actions might sound pretty typical for a nurse, but Candice actually wasn’t hired as a nurse. Candice worked as a custodian, but she infused the typical procedural parts of her day with her own unique perspective—one that helped other people and filled her own hours with the sustenance of meaning. Caretaking wasn’t in her job title or description, but she did it anyway. Not only did Candice comfort and care for the sick with compassionate love and thoughtfulness, but she also reshaped her career experience to fulfill her particular traits and desire for purpose.

Finding meaning looks much simpler than moving to another country, switching majors, or transferring careers. Before you uproot your life, take a moment to assess the way you live and identify spots in your day you may be able to fill with greater purpose. Take a look into the hours of your week to see where delight is missing and where it may soon grow again.

Beliefs, assumptions, and lifestyles grow stale if they sit in complacent acceptance. Taking another glance at the things you accept unquestioningly reveals the spots that need some touching up and the areas where you might begin to see reality anew.

|

|

This newsletter is powered by Thinkr, a smart reading app for the busy-but-curious. For full access to hundreds of titles — including audio — go premium and download the app today.

|

|

Was this email forwarded to you? Sign up here.

Want to advertise with us? Click

here.

|

Copyright © 2026 Veritas Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved.

311 W Indiantown Rd, Suite 200, Jupiter, FL 33458

|

|

|