Key insights from

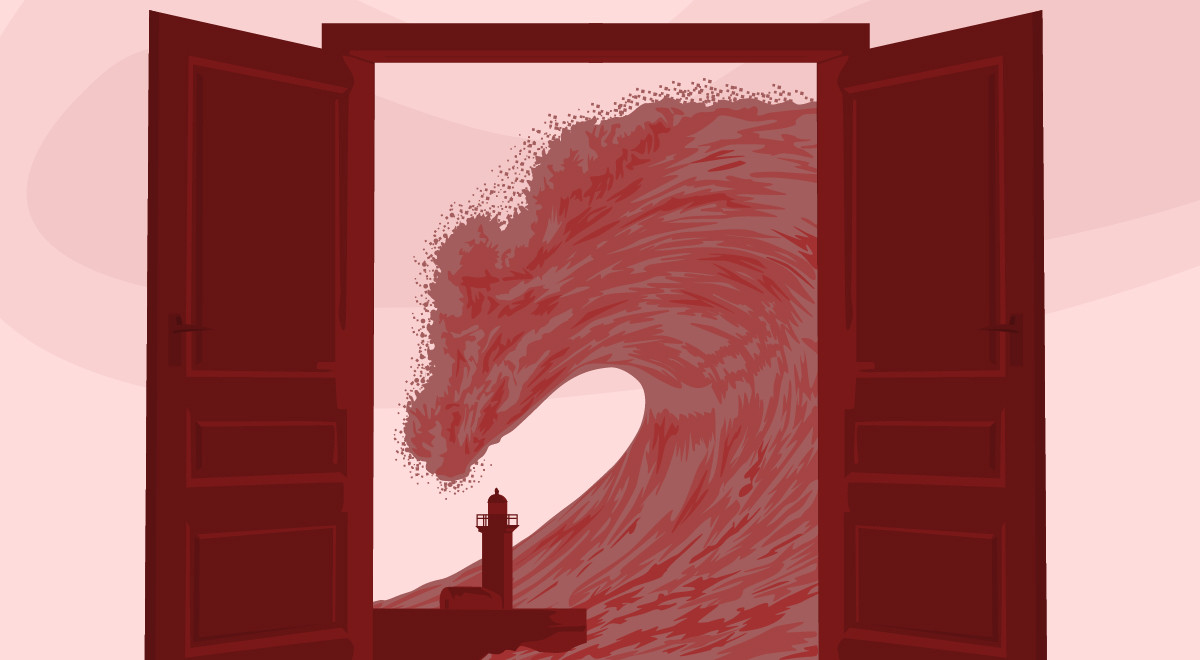

The Doors of the Sea: Where Was God in the Tsunami?

By David Bentley Hart

|

|

|

What you’ll learn

One of the most challenging objections to God is also one of the most ancient ones: How could a good God allow such evil and suffering? Is he not powerful enough to stop it? Or, if he is, why doesn’t he? Natural disasters like tsunamis and earthquakes inevitably evoke questions about and interrogations of the divine. Scholar David Bentley Hart invites Christians to allow the weight of the world’s horrors to affect them even as they hold to the hope that God will bring his kingdom, where suffering and evil find no place.

Read on for key insights from The Doors of the Sea.

|

|

1. In moments of tragedy, when words fall short, it’s probably best that we fall silent.

In 2004, a devastating earthquake struck Southeast Asia with a force of 9.0 on the Richter scale. The epicenter was the Indonesian island of Sumatra. The tremors themselves were devastating, but even more ruinous were the tsunamis that emanated from Sumatra. Entire villages were leveled, the vegetation of whole islands was ripped up and carried off, families were separated, and many never reunited. Most did not see it coming. Even 1,500 miles away from the quake’s epicenter, Sri Lankans had no warning that devastation was silently gliding toward them.

It was more than a few days before the rest of the world got an accurate sense of the damage that the earthquake and resultant tsunamis had caused. The death toll began in the tens of thousands and then climbed to over a hundred thousand. According to the latest estimate, the death toll is 250,000. Satellite imagery revealed ravaged coastlines, full of flotsam, jetsam, and the corpses of men, women, and children. Lots of children.

When we encounter tragedy—especially tragedy of this scale, it’s better we refrain from interpreting the event. Attempts to make meaning or meaninglessness are petty and above our metaphysical pay grade. Even well-intended words of consolation can be grating—almost obscenely so. In times when words fall short, it’s probably best that we fall silent.

But we seem unable to stop ourselves.

|

|

2. The responses of skeptics to tragedy are sometimes more Christian than Christians’ responses.

Sometimes we honor the dead best with respectful silence. But silence is difficult for us. Many use calamity as an opportunity to score points for their personal philosophy.

Some atheists gleefully leapt into the fray to denounce the existence of a God of love—or a God at all. The tsunamis were followed by tidal waves of materialist op-eds.

Most arguments that atheist journalists posed in the wake of the disaster were painfully simplistic and careless. They tended to assume a view of God that Christianity does not adopt. If we are honest with ourselves as to whether the most recent natural disaster has something new to teach us about life and the world, the answer, quite frankly, is “no.”

We can’t sidestep the confusion or the deep sadness of such events, but neither can we neatly divine their meaning. Christians should start expecting that some atheists will look to score points for Team Materialism. And as annoying as some may seem, as facile as many of their arguments for God’s non-existence might be, it’s an opportunity to bear with others in the spirit of Christian love.

Given our finite human perspective, we cannot know with any certainty what the meaning of events is or how they fit into the grander, cosmic scheme of things. We can hate God for tragedy, we can reject him, but tragedies are not sufficient grounds for disproving him.

It is certainly odd that some atheists wait expectantly for the latest natural catastrophe to crush faith in God for good—as if during 2,000 years of persecution, plague, famine, war, and illness, Christians had never wrestled with the very real problems of evil, death, and pain. But while it might be cathartic to dismantle ruthlessly and then walk away from some atheists’ arguments, it dehumanizes both parties.

We must recognize the irony beneath even the most strident atheist’s eager rejection of God: that it is a response to tragedy that is shaped by the Christian imagination of God and how the world should be. The atheist is allowing the genuine shock and weight of a calamity to sink in instead of avoiding it with a glib platitude. He sees pain and believes that it shouldn’t be this way. This is an opportunity for the Christian to empathize and connect—not score points.

In this regard, the Christian would even do well to learn from some atheists. In some ways, feeling the pain and expressing the anger of tragedy is a more “Christian” response than the response of professing believers. In tragedy, some atheists exemplify certain aspects of the Christian faith better than Christians do—though both parties are reluctant to admit it.

|

|

3. Not all arguments against God are created equal.

Some formulations of the problem of evil should make us pause more than others. The arguments of atheist journalists immediately following the earthquake and tsunamis were unsophisticated and not even worth the fight. The idea that they have of God is more an Enlightenment deist variety of God than the God of the Christian doctrine and imagination. (Unfortunately, many Christians themselves have lost touch with the God of Christianity over the centuries.)

The eighteenth-century French philosopher Voltaire made similar arguments centuries ago, but with far more wit and verve. An earthquake of similar magnitude to the Sumatra earthquake rocked Lisbon, Portugal, in 1755. Tremors were felt all the way in North Africa and Scandinavia. The city was engulfed in flames, and tidal waves ripped through the coastal regions of the country. An estimated 60,000 people died.

Voltaire wrote a blistering 234-line poem about the event in which he juxtaposes images of post-tsunami carnage and terror with the metaphysical optimism of his day that believed we live in “the best of all possible worlds.” How, Voltaire probes, could natural disasters that level a city, decimate its population, and incur tremendous grief be good and necessary for the whole? Would the world actually be worse off if the disasters didn’t strike? That seems incredible to Voltaire, and his caustic satirical style adds strength to a troubling moral dilemma.

Even Voltaire’s arguments, though, become less formidable when we consider his searing critique is of a God not found in Christian doctrine. He is coming after a God who directly wills and orchestrates all causes and effects in the universe, where everything that happens is exactly as God intends and superintends. It’s an understanding of God that does not consider the basic elements of Christian faith, like humanity’s isolation from God as a result of creation’s rebellion, of how this world is a shadow of what God intended (and intends) it to be, enslaved to spiritual and earthly powers that actively oppose God.

In short, Voltaire was taken in by the Enlightenment’s charms, and he addressed a post-Christian Europe that had not yet abandoned the idea of God entirely. Voltaire was a deist, and he was criticizing a concept of God that isn’t nearly as germane to our own day.

While all this is true, the Christian cannot honestly ignore Voltaire’s complaint either. In his (and atheist journalists’) expectations that God is supposed to be good, the Christian must recognize the rough contours of the God we come to know in Christian doctrine. In a round-about way, the atheist, with indignation at pat answers like “God’s will” and disgust that God could be connected to such evil and suffering, shows more reverence for God than some Christians do.

|

|

|

|

4. The strongest argument against God’s goodness was made by a devoted Christian.

Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821-1881) wrote a masterpiece of a novel called The Brothers Karamazov. Through one of his characters, Dostoevsky gives voice to an argument that carries far more force than the clumsy arguments of atheist journalists in the aftermath of a tragedy, and it’s far more disturbing and potent than Voltaire’s “Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne.”

In the novel, the argument comes in the form of a lengthy discussion between two brothers, in which Ivan lays out for his brother, Alyosha, his moral grievances against God.

Ivan’s argument is an extremely sophisticated one. He rejects salvation of the world that God offers if the suffering of children would be part of bringing it about. He cites to Alyosha a long litany of horrible cases of children abused and murdered (based on headlines from real newspaper articles that Dostoevsky had collected). In one case, parents routinely beat their daughter, filled her mouth with excrement as punishment for soiling her bed, and then locked her in the outhouse in the dead of Russian winter.

How, Ivan asks, can he bring himself to accept that God is good if this poor young girl’s torture and suffering are part of his grand plan? This is not a clumsy tirade. It’s not the argument of an unbeliever, but a dissident. Ivan acknowledges that God might, in fact, exist. The fact that a brute animal like man could even conceive of something like “God” is reason enough to avoid blithe dismissals of God as a fable. Ivan is even willing to grant that there will come a time when God will put all things to rights, when tears will be wiped away, when all will be made new, when universal harmony reigns. But for Ivan, what happens in a distant realm someday in the distant future is something he feels morally obliged to reject if that little girl’s suffering was needed to bring it about.

In effect, Ivan says, “thanks, but no thanks” to God and salvation. The cost is unacceptably high—whatever future bliss God has in mind for his creatures. Even if justice is discharged, and this future realm is filled with grace enough for children to happily forgive their torturers, even if God reveals universal truth that shows how all the threads of the tapestry fit together, his own conscience prevents Ivan entering into such a kingdom.

Ivan’s argument is one that any genuine believer must take seriously. Those believers who can ignore it or sidestep it without considering what Ivan is proposing are probably following Christian doctrine that’s taking them away from the God who revealed himself in Christ.

And here’s another remarkable dimension of Ivan’s argument against a good God’s existence: Dostoevsky uses his character Ivan to draw his reader into a more genuine expression of Christian faith. It comes against metaphysical optimism, fatalism, and meaningless logical determinism. It’s a call to the Christian to venture into a profounder, more revolutionary understanding of God and evil, that evil is utterly outside the nature of God, that suffering and acts of evil are, quite frankly, meaningless, in and of themselves. Evil is never an exertion of God’s will upon creation.

The shadow that is Ivan’s argument is especially dark because of the light of the gospel. Over the course of the novel Dostoevsky deals with the objections that his character Ivan raises, but not in the form of scientific or rational proof, as a skeptic or fundamentalist might demand. It’s an artistic response, in which, over hundreds of pages of story, Dostoevsky shows us the life of a priest, Father Zosima. Father Zosima displays humility, gentleness, and humanizing kindness. He acknowledges that God’s methods of redemption are mysterious, but that God doesn’t use children’s suffering as means to an end of his glory. Such suffering is evil to the core.

In his brilliance, and with a subtlety that could only come from someone with deep faith, Dostoevsky simultaneously presents the strongest challenge to belief in God’s goodness and a vigorous expression of belief in a God who is all-merciful and an insistence that he be good. This pairing pushes us to more genuine expressions of faith than a belief that can write off suffering with a tidy bit of logic or optimism.

|

|

5. Calvinism’s pre-determinism complicates the problem of evil by insisting that God is evil’s author.

In the wake of the tsunamis over the Indian Ocean, it was not only atheists ready to connect evil to this entity Christians call God. Some Christians themselves stubbornly refused to disconnect God from evil. Many of these were from the particularly rigid Calvinist quarters.

Theologies that give a disproportionate priority to God’s omnipotence can bring arguments to absurd conclusions. Such are some of John Calvin’s arguments. In Book III of The Institutes of the Christian Religion, Calvin argues that God’s glory and power are displayed both through his saving some and his damning others in accordance with his predetermined will.

In his fretful eagerness to guard God’s holiness and power against one iota of human volition, Calvinist doctrine makes God the author of evil. Not only do Calvinists make God evil’s author, they inadvertently make God himself evil, because there’s no clear distinction between God and his universe, between his will and his creation’s will. In reality, creation has its own connected, but distinct identity. By refusing to make this distinction, the Calvinist makes God one with his creation—with people, with the world, with Satan, and with his minions.

True freedom of God’s creatures to choose between God and the shadowy non-existence of hell is essential to prevent all of creation (and all its attendant evils) from being an extension of God.

A deterministic view of God that tries to corral everything in the universe into God’s will ends up capturing nothing of what life is like. Saying, “It’s God’s will” is basically saying “It is what it is,” with a thin theological overlay. It’s an inane tautology. By trying to say everything, one says nothing. Freedom is part of God’s creation, and it is this freedom that recognizes the mystery both of the divine will and human freedom. An entire chain of cause-and-effect issuing from one central transcendent source will leave no room for divine intervention or human liberty.

Ivan Karamazov’s argument against God gains strength when pitted against cheap theodicies and theological determinism. It ensures that God has not only used a young Russian girl’s torture to bring about universal harmony, but he has willed that the torture take place. The Calvinist view refuses to decouple God from evil, and, in the process, does great injury to the Christian imagination and our understanding of God’s intentions toward creation. From doctrines like these spring more confusion among both believers and the skeptics trying to make sense of pain and disaster.

In the aftermath of tragedy, respectful silence honors the dead better than scoring intellectual points for one’s preferred position. There’s great confusion and sadness, and divine purposes remain mysterious. What is far more certain, however, is that it is outside the character of God to author evil. Pain and suffering, in and of themselves, are meaningless, and we haven’t seen the last of it until God ushers in universal harmony with the coming of his kingdom.

|

|

This newsletter is powered by Thinkr, a smart reading app for the busy-but-curious. For full access to hundreds of titles — including audio — go premium and download the app today.

|

|

Was this email forwarded to you? Sign up here.

Want to advertise with us? Click

here.

|

Copyright © 2026 Veritas Publishing, LLC. All rights reserved.

311 W Indiantown Rd, Suite 200, Jupiter, FL 33458

|

|

|